Donna chi era costei

DONNA CHI ERA COSTEI

2022

Cortesia di Maja Arte Contemporanea

Testo di Isabella Ducrot

“Woman: who was she?”

by Isabella Ducrot

Art gallery Maja Arte Contemporanea is hosting an exhibit featuring the most recent sculptures by Janine von Thüngen. The timely urgency in these works charges this exhibit with added potency, which goes to enrich the artist’s well known exuberance. This is not just any exhibit precisely because of this historical moment. The coincidence of events is poignant. On the one hand, a Roman art gallery displays vibrant statues of female nudes, in a quiet street in the city centre; on the other, on the margins of Europe, what one might simply call ‘war’ has broken out. The novelty is that, for the first time, this war is a spectacle that can be observed in real time in places at peace.

Unexpectedly, the exhibition acquires new poignancy and new, layered meaning; implicitly, it poses probing questions. For example, ‘how can a society filled with liberated women (artists) still see war as inevitable and, in traditional terms, a male affair?

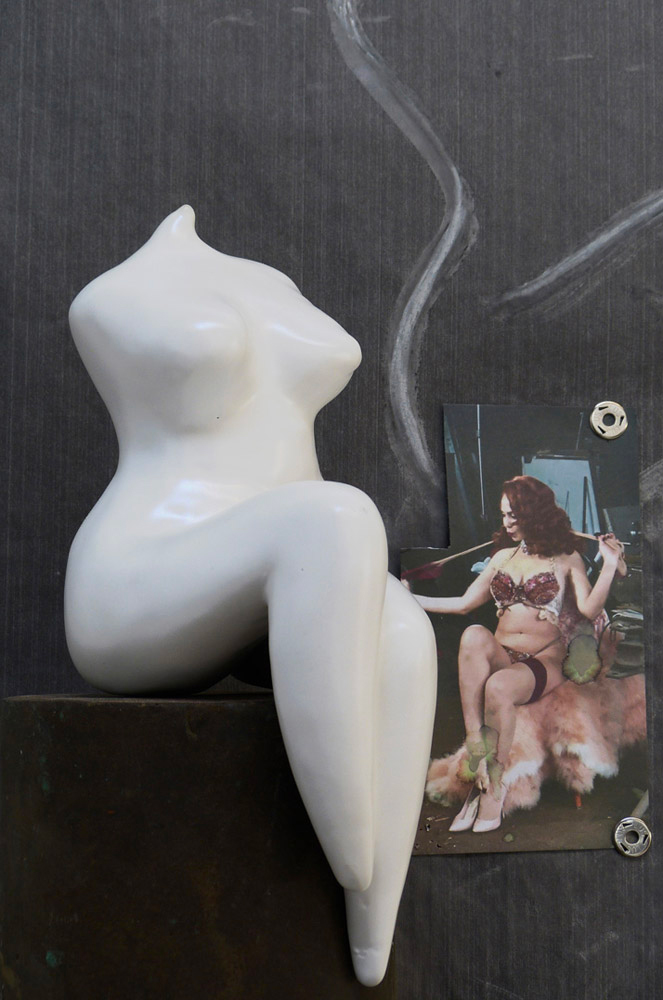

Janine von Thüngen’s sculptures should be observed carefully: the female nudes, sculpted out of different materials, occupy space as a multitude of question marks. They demand responses, obstinately, never seeking to be reassuring. They seem to come out of their shell, asking for clarifications and implying a collective state of mind, one shared by all today. ‘Today’ then becomes a time more ‘present’ than usual, one whose incandescence with probably only be fully understood in the future. Perhaps, given the incumbency of the events to which we are subjected, this ‘Today’ is not a time for answers. And again it is still a time to wonder: ‘how do we, as women, live the unrest in the current al leged normality?’. These sculptures seem to suggest that in a distant future new women may be able to turn back and ask: ‘Women, who were they?’

The artist cannot ignore all of this; yet she does not seem intent on finding a coherent answer. ‘But ask them!’’ Them are her works of art: they ought to know; hence, to them we turn. Those exuberant bodies are all incomplete, while some also have something more. One can find, the trace of male genitals, a missing head — as is the case for all the statues —, an emphatic portrayal of breasts — the most evident female part — with one having three breasts. The latter makes us dream; it seems to announce, ‘here is abundance, and then more’ and seemings to claim that the power to nourish should never be underestimated.

Evidently, almost seductively, each of these statues, whether big or small, combines opposite personalities. The women are bold, liberated, free from allusions to edenic deities or sacrality. They resemble larger, budding girls who boldly take up space on busses with their summer clothes barely containing them. Yet in spite of their assuredness and determination, these statues are headless. It does not seem as though they have lost their head, but rather as if they never had one.

To the potential question, raised by future women: ‘Women: who were they?’ there will be answers which we are not allowed to give today; that is the mystery of our present time. We cannot know now how we were.

-

- Donna chi era costei’ 2022 Bronze white hot dip varnishing 27 x 8 x 8 cm 10,5 x 25 x 9 cm ed. 8 | Courtesy Maja Arte Contemporanea

-

- Donna chi era costei’ 2022 Bronze white hot dip varnishing 27 x 8 x 8 cm 10,5 x 25 x 9 cm ed. 8 Courtesy | Maja Arte Contemporanea

-

- Donna chi era costei’ 2022 Bronze white hot dip varnishing 27 x 8 x 8 cm 10,5 x 25 x 9 cm ed. 8 | Courtesy Maja Arte Contemporanea

-

- Donna’, 2022 Mixed media 3D PRINT, white coating height 240 cm x width 68 cm x depth 90 cm. Courtesy collection CARPE, Antwerp

-

- Donna chi era costei , 2022, 3D PRINT, white coating height 80 cm x width 30 cm x depth 30 cm , private collection, USA.

-

- Donna chi era costei 2022, Mixed media 230 x 76 x 65 cm also available in bronze courtesy Maja Arte Contemporanea